OCTOBER 25, 2021 – By Hugh Stephens

In the past several years there has been an exponential explosion of content in the audio-visual space driven primarily if not almost exclusively by online streaming services, both national and international. Names such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney +, Paramount +, HBO Max, Hulu and many more are well known to consumers around the world as providers of first-class entertainment content. The greatest beneficiary of this content cornucopia has been the consumer who is enjoying expanded access to a wider range of material than ever across various genres—drama, kids, light entertainment, documentaries—all provided in many different languages and representing various cultures and locations. And it is not just the consumer who has benefited. Content producers and all related aspects of the content industry eco-system have ridden this wave.

Greater consumer demand has driven the need for more production, which in turn has created more opportunities for writers, producers, actors, stuntmen, foley artists, caterers, animators, technicians, and all the elements that go into producing movie and TV series for the Video On Demand (VOD) industry, as well as for the studios themselves. Given the wide range of geographic locations where production is taking place, this production is building national capacity in both hardware (sound stages, animation studios, filming facilities) and software (trained people, skilled professionals, artists, creators, and so on).

Regulators and Streaming

At the same time, broadcast regulators in governments around the world are trying to come to grips with the new phenomenon of streaming as legacy broadcast media sees a significant shift away from “viewing by appointment” to “viewing on demand”. For decades regulators have crafted and applied a set of rules around broadcasting based on the issuance of licences, initially to use government-controlled spectrum and later to distribute content through nationally regulated cable and satellite distribution services. However, streaming is a different breed of cat, sometimes based offshore but delivered through regulated infrastructure (the telcos); sometimes locally incorporated but not covered by broadcast regulations.

What should the response of regulators be to this new kid on the block? Regulators are mandated to protect national interests, which often includes policies to protect and promote national identity and culture, in addition to elements of social welfare such as protection of children and consumers. One solution could be to extend broadcast regulation to the streaming sector, arguing on the basis of the “level playing field” that all content producers should play by the same rules. Another would be to recognize that there are some inherent differences between regulated (and protected) broadcasting services, and streaming services, and instead to work with the streamers to maximize benefits for each economy and society. This can be achieved by avoiding the kind of restrictive regulatory structures that national broadcasters have contended with, and which increasingly don’t support a healthy broadcast industry.

IIC Panel on Video Streaming

This issue was explored in depth at the recent 51st annual meeting of the Institute for International Communications (IIC) held virtually from London from October 5-7. Founded at Ditchley Park in the United Kingdom in 1969 to promote international dialogue about communications, the IIC is the longest established global, independent, non-profit organization of its kind. The final panel of the conference was a “video streaming roundtable”, an informative discussion of the issues surrounding growth of the VOD sector. It featured a regulator (José Fernando Parada Rodríguez, Audiovisual Content Commissioner, Commission for Communications Regulation, Colombia), an academic (Dr. Maria Michalis, Associate Professor in Communication Policy, University of Westminster), and two industry representatives (Facundo Recondo, Vice President, International, External & Regulatory Affairs for Caribbean, Central and Latin America, AT&T and Joe Welch, Vice President Global Public Policy, Asia Pacific, The Walt Disney Company) both from companies that have been extremely active in the VOD space. The panel was moderated by Clive Kenney, Manager, Telecoms, Media and Digital Practice, for Frontier Economics. Kenney was well informed on the issues at play, Frontier Economics having just concluded a series of detailed studies on the impact of streaming’s growth on local content.

This issue was explored in depth at the recent 51st annual meeting of the Institute for International Communications (IIC) held virtually from London from October 5-7. Founded at Ditchley Park in the United Kingdom in 1969 to promote international dialogue about communications, the IIC is the longest established global, independent, non-profit organization of its kind. The final panel of the conference was a “video streaming roundtable”, an informative discussion of the issues surrounding growth of the VOD sector. It featured a regulator (José Fernando Parada Rodríguez, Audiovisual Content Commissioner, Commission for Communications Regulation, Colombia), an academic (Dr. Maria Michalis, Associate Professor in Communication Policy, University of Westminster), and two industry representatives (Facundo Recondo, Vice President, International, External & Regulatory Affairs for Caribbean, Central and Latin America, AT&T and Joe Welch, Vice President Global Public Policy, Asia Pacific, The Walt Disney Company) both from companies that have been extremely active in the VOD space. The panel was moderated by Clive Kenney, Manager, Telecoms, Media and Digital Practice, for Frontier Economics. Kenney was well informed on the issues at play, Frontier Economics having just concluded a series of detailed studies on the impact of streaming’s growth on local content.

Market Studies

These studies looked at ten different markets (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Korea and Taiwan) and summarized research that Frontier Economics has recently done to examine the economic impact that protectionist policies can have on video content production, while highlighting the positive impact that VOD providers have had in each of these markets. During the IIC panel presentation, Disney’s Welch spoke specifically about the case of Australia. He pointed out that competition for VOD subscribers is driving local content creation. As each new VOD player has come into the market, beginning with STAN (a local streaming service), followed by Netflix, then Amazon, Disney +, and so on, there has been increasing investment in local content. Disney, for example, initially competed with content from its US service, but soon needed to pivot to local content. The result is industry spending of $268 million on local content productions in Australia in 2020.

Australia as a Case Study

Welch recounted how Disney’s offerings in Australia fall into three categories; (1) all Australian production produced in Australia through ABC Studios International, both for the domestic Australian market and for export (2), production in Australia with some Australian content (writers, actors etc.) although the story is set outside Australia and (3) production filmed in Australia that, on its surface, has no obvious Australian content. Marvel Movies such as Shang-chi and Thor are examples of the latter category. All three contribute to the strength of Australian production and complement one another. Even sci-fi or superhero films that have no direct Australian flavour not only keep film workers employed, they hone skills, enhance capacity and have significant economic impact. The impact on local platforms is also positive. Domestic telcos in Australia have enjoyed strong revenue growth from digital consumption and from partnering with international VOD providers. The same impact is found in other markets, such as India, Indonesia, Taiwan, and Korea, as documented by the Frontier Economics studies.

The Korean Example

Korea is a good example. Korean films and television series have dominated the box office and TV viewing in Korea for the past couple of decades, ever since the abolition of the screen quota that required a set number of days be set aside in theatres for showing Korean films, a policy that often left cinemas dark for want of content. Korean drama has also been popular in neighbouring Asian countries but with streaming, Korean content has now gone global with the much-talked-about Squid Game, distributed on Netflix. VOD is also thriving at home. Nearly 9 million Koreans subscribed to VOD in 2020 and over 50% of Korean internet users use VOD at least once a week spending almost two thirds of their time consuming local content. VOD services are investing in local content and thereby creating jobs and delivering returns for the local economy. The global reach for Korean content that streaming services provide brings additional returns to the Korean economy through tourism and by projecting Korean culture on a world stage. The Frontier Economics findings for Korea are similar to the results from their other studies of national markets. A launch event hosted on August 30, involving representatives from local VOD service Tving, Kim Jong-Hak Productions, Chung-ang University and the filmmaking community, concluded that VOD operators should be able to self-classify content, rather than leave it to a ratings board that simply could not meet the deadlines for rating all streaming content.

While not raised during the IIC panel, the launch of the Indonesia report on September 6 — which involved a roundtable moderated discussion with leading Indonesian producers — was notable for comments made by guest speaker Sandiaga Uno, Minister of Tourism and Creative Economy, who said, “VOD is taking center stage. It could be defined as a pandemic winner, and we believe, as a government, that when things are doing well, we should not come in and try to regulate or try to fix it when it is not broken.”

[1] Launch of The Economic Impact of Video On Demand Services in Korea

[2] Launch of The Economic Impact of Online Curated Content Services in Indonesia

Global Investment in Streaming Content

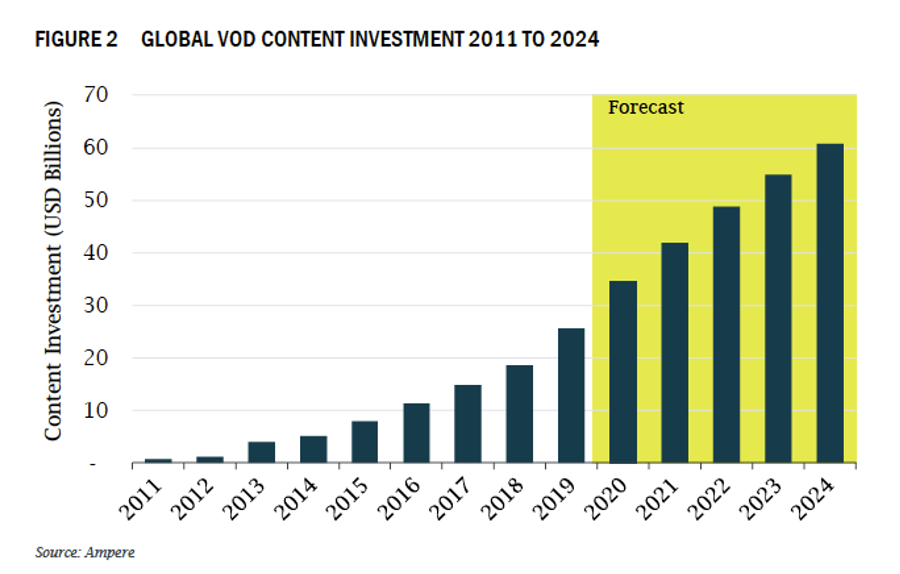

Globally, investment in streaming content more than doubled from 2017 to 2020, increasing from $15 billion to approximately $35 billion and is estimated to reach over $60 billion by 2024.

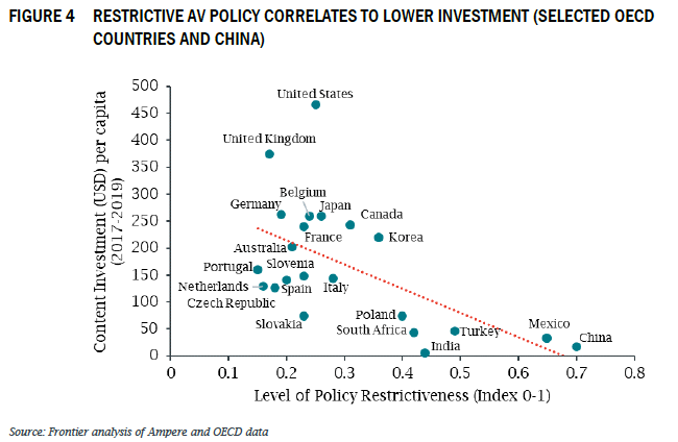

Frontier Economics also pointed out that protectionist policies can work against the virtuous circle of increasing investment. Policies that shield local companies from international competition can result in local content industries that are less innovative and less able to produce the kind of high-quality content that is in demand internationally. Frontier’s analysis found that more stringent protectionist policies, such as content quotas, leads to reductions in exports of audio-visual products. Countries that have greater policy restrictions tend to have lower levels of investment in content.

Impact of Protectionist Policies

While protectionist restrictions can have a number of legitimate policy objectives (such as whether to support the creation or consumption of local cultural content or to help the home-grown AV sector), they can also have adverse impacts. These include restrictions that can drive up costs for domestic and foreign companies resulting in reduced competition and increased prices for consumers, and policy restrictions that erect barriers to inward investment which can deter the inward flow of international capital, talent and skills, resulting in restricting the arrival of new techniques and innovations. In addition, onerous definitions of “local content” can discourage investment in local content and protectionist content measures can have the perverse effect of encouraging piracy, as consumers seek to access content outside of legitimate channels. And a new, emerging area of debate is around protectionist policies that benefit national telcos with mandatory “network fees” from content service providers, including VOD services, at the expense of consumers, effectively allowing telcos to be paid twice (both by their users/subscribers and by content service providers) for the same network usage.

Broadcast Quotas

Broadcast quotas are another protectionist policy that needs careful review. They are usually designed to nudge consumers towards local content but implementing them for VOD services can be problematic. Quotas can produce a number of counter-intuitive outcomes. For example, they may not be effective in changing consumer tastes, as viewers select content on demand. They can distort incentives as producers may focus more on quantity and less on quality, leading to lower-quality production that has less of an economic impact and less international appeal. Content quotas may also result in VOD services reducing the scope of their overall repertoire in order to meet local content requirements for the local content that they are able to licence, thus reducing choice for consumers.

These issues were all explored in the IIC session. It was pointed out that global companies have a choice as to the location of production. The policy environment in a given jurisdiction can promote or hinder investment, which in turn will have an impact on production of local content. Jose Parada Rodriguez, Commissioner for Audiovisual Communications at Colombia’s communications regulatory body argued that regulators should promote competition, not protect existing business models. With regard to the “level playing field” question between new streaming services and legacy broadcasters, Joe Welch commented that the question is whether onerous obligations that were perhaps appropriate for an earlier age of regulated broadcasting should be expanded to streaming services. Instead, perhaps the obligations on broadcasters should be modified and updated to make them more relevant to the digital age?

The Future of Streaming

The data produced by Frontier Economics in its market studies has helped to underline the positive impact on local content production of the investment brought by international VOD services. Sensible regulation can make a difference. Policies that promote inward investment and allow the creative juices of AV producers to flow provide a range of benefits to consumers, local economies and culture, domestic production facilities and artistic output. Heavy-handed regulation and imposition of legacy conditions on new streaming services is counter-productive. The correlation between more restrictive regulation and lower investment in production is compelling. The IIC’s VOD panel did a good job of shining a spotlight on these issues. Let’s hope that governments and regulators are listening. The health of local content production, and the needs and expectations of consumers, depend on it.

Hugh Stephens is a commentator on international copyright and content issues. Based in Victoria, BC, Canada, he writes a weekly blog (www.hughstephensblog.net) “Insights on International Copyright Issues”. He served as Senior Vice President (Public Policy) for Asia Pacific for Time Warner from 2001-2009, after a 30 year career in the Canadian foreign service during which he served in Lebanon, Hong Kong, Beijing, Islamabad, Seoul and Taipei.